重于天堂全文高清英文版.pdf

http://www.100md.com

2021年2月3日

|

| 第1页 |

|

| 第4页 |

|

| 第18页 |

|

| 第28页 |

|

| 第50页 |

|

| 第221页 |

参见附件(14821KB,503页)。

一颗子弹,一声枪响,一段悲剧的童年时光。

权威音乐记者查尔斯·R. 克罗斯历时四年写就的传记

再现科特·柯本短暂而炽烈的生命轨迹

亚马逊年度畅销书籍

★《重于天堂》为所有音乐人物的写作设立了一个新的高度。——《滚石》

★有史以来关于摇滚明星最为动人和坦诚的书籍之一。——《洛杉矶时报》

内容简介

本书是美国著名音乐记者查尔斯·R. 克罗斯写就的权威科特·柯本传记。作者通过4年的调查、400多次采访以及对柯本未出版的日记、歌词和家庭照片等珍贵资料的抽丝剥茧,生动再现了这个传奇摇滚巨星短暂而炽烈的生命足迹——从悲惨的童年到孤苦的青春期,再到在阿伯丁进行音乐探索的日子,直至最终成名后在公众和媒体的巨大压力下自杀身亡。《重于天堂》不仅为读者呈现20世纪八九十年代美国地下摇滚乐的辉煌群像,更将其中心人物科特·柯本不为人知的一面重新发掘出来——这不仅是一个充满争议的音乐巨星的故事,更是一个始终渴望爱的、孤独的孩子的故事。

作者简介

★作者:查尔斯?R?克洛斯

Charles R. Cross (1975—)

美国西雅图音乐与娱乐杂志《火箭》编辑。著有《满是镜子的房间:吉米·亨德里克斯传》《重于天堂:科特·柯本传》等多本与摇滚乐相关的著作。

★译者:牛唯薇

译有《西雅图之声》《十三座钟》等。

前新闻狗,想当编剧/作家。

预览图

目录

作者的话

序言 重于天堂

第一章 幼年时光

第二章 我恨妈妈,我恨爸爸

第三章 当月之星

第四章 草原带牌香肠男孩

第五章 本能的意志

第六章 不够爱他

第七章 裤裆里的酥皮·希尔斯

第八章 重返高中

第九章 人类过多

第十章 非法摇滚

第十一章 糖果,小狗,爱

第十二章 爱你太深

第十三章 理查德·尼克松图书馆

第十四章 烧烧美国国旗

第十五章 每当我吞下

第十六章 刷牙

第十七章 脑子里的小怪物

第十八章 玫瑰水 尿布味

第十九章 那场传奇的离婚

第二十章 心形棺材

第二十一章 微笑的理由

第二十二章 柯本病

第二十三章 就像哈姆雷特

第二十四章 天使的头发

尾声 伦纳德·科恩的来世

鸣谢

Chapter 4

PRAIRIE BELT SAUSAGE BOY

AEERDEEN.WTASHI NGTON MARCH 1982 -MARCH 1983

Don’t be afraid to chop hard, put some elbow grease in -From the cartoon “Meet jJimmy, the Prairie Belt Sausage Boy.”

It was at his own insistence that in March 1982, Kurt left 413 Fleet Street and his father and stepmother’s care. Kurt would spend the next few years bouncing around the metaphorical wilderness of Grays Harbor.. Though he d make two stops that were a year in length, over the next four years he would live in ten different houses, with ten different families. Not one of them would feel like home.

His first stop was the familiar turf of his paternal grandparents' trailer outside Montesano.From there he could take the bus into Monte each morning, which allowed him to stay in the same school and class, but even his classmates knew the transition was hard. At his grandparents, he had the sympathetic ear of his beloved Iris, and there were moments when he and Leland shared closeness, but he spent much of his time by himself.It was yet another step toward a larger, profound loneliness.

One day he helped his grandfather construct a dollhouse for Iris’s birthday.Kurt assisted by methodically stapling miniature cedar shingles on the roof of the structure. With wood that was left over., Kurt built a erude chess set. He began by drawing the shapes of the pieces on the wood, and then laboriously whittling them with a knife.Halfway through

this process, his grandfather showed Kurt how to operate the jigsaw, then left the fifteen-year-old to his own devices, while watching from the door. The boy would look up at his grandfather for approval, and Leland would tell him, “Kurt, you’re doing good.”

But Leland was not always so kind with his words, and Kurt found himself back in the same father/son dynamic he’d experienced with Don. Leland was quick to pepper his decrees to Kurt with criticism In Leland’s defense, Kurt could truly be a pain. As his teenage years began, he constantly tested his limits, and with so many different parental figures-and none with ultimate authority over him-he eventually wore out his elders. His family painted a picture of a stubborn and obstinate boy who wasn’t interested in listening to any adults or working. Petulance appeared to be an essential part of his nature, as did laziness, in contrast to everyone else in his family-even his younger sister Kim had helped pay the bills with her paper route..“Kurt was lazy, " recalled his uncle Jim Cobain.“Whether it was simply because he was a typical teenager or because he was depressed, no one knew.”

By sumeer 1982, Kurt left Montesano to live with Uncle Jim in South Aberdeen.His uncle was surprised to be given the responsibility. “I was shocked they would let him live with me, ” Jim Cobain remembered.“I was smoking pot at the time.

I was oblivious to his needs, let alone to what the hell I was doing." At least, with his inexperience, Jim was not a heavy-handed disciplinarian. He was tmo years younger than his brother Don but far hipper, with a large record collection:“I had a really nice stereo system and lots of records by the Grateful Dead, Led Zeppelin, and the Beatles.

And I’d crank that baby up loud."” Kurt’s biggest joy during his months with Jim was rebuilding an a plifier.

重于天堂全文截图

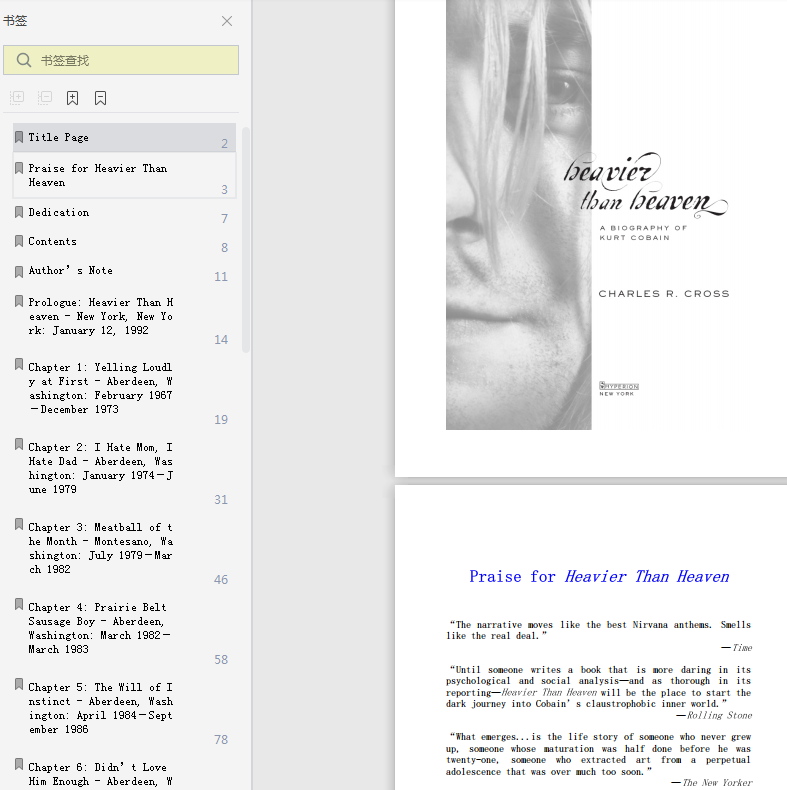

Praise for Heavier Than Heaven

“The narrative moves like the best Nirvana anthems. Smells

like the real deal.”

—Time

“Until someone writes a book that is more daring in its

psychological and social analysis—and as thorough in its

reporting—Heavier Than Heaven will be the place to start the

dark journey into Cobain’s claustrophobic inner world.”

—Rolling Stone

“What emerges...is the life story of someone who never grew

up, someone whose maturation was half done before he was

twenty-one, someone who extracted art from a perpetual

adolescence that was over much too soon.”

—The New Yorker

“The results of Cross’ assiduous reporting show through in

every chapter. A remarkable portrait.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“One of the most moving and revealing books ever written

about a rock star. An invaluable look at the life of a

troubled artist.”

—Los Angeles Times

“In his early teens, Cobain told a friend, ‘I’m going to

be a superstar musician, kill myself and go out in a flame of

glory.’ This well-reported book... provides the most

grounded account of how Cobain, not too many years later, did

just that.”—The New York Times Book Review

“The biography that the most important rocker of his

generation has always deserved: exhaustively researched, full

of insight into the ‘real’ Cobain as opposed to the

manipulated media image, and written in a clear and

compelling... voice.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“A cautionary tale of a talented, lucky musician who became

fatally confused about whether fame was a reward or a death

sentence.”

—People

“No other book on Kurt Cobain matches Heavier Than Heaven

for research, accuracy and insider scoops.”

—The New York Post

“By keeping a steady eye on the facts, Cross mostly pierces

the rumors, hype and conspiracy theories that have long

confounded Nirvana’s place in history...At last, perhaps,Cobain’s ghost can find some peace.”

—The Miami Herald

“Charles R. Cross takes readers deeper into the life of the

brilliant, troubled Kurt Cobain than anyone thought possible.

The result is more than just an excellent book... Cross helps

reset the standards of what biographies—not just rock bios—

should be.”

—The Rocky Mountain News

“Shakes up the prevailing conceptions of Cobain...A

compelling biography.”

—Biography

“A fascinating, if sometimes frightful, read, a full-scale

work that manages to be respectful of Cobain’s unlikelytriumphs from poverty and also critical of his stunning

excesses.”

—The Seattle Post-Intelligencer

“A standout among rock bios and deserves its place in pop-

culture collections.”

—Booklist

“Cross treats the strange, unhappy life of musician Kurt

Cobain with intelligence and an insider’s perceptiveness.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A thorough, cogent look at Kurt Cobain...No other book

matches Heavier Than Heaven for research, accuracy, and

insider scoops.”

—The Seattle Times

“Cross transcends the other Cobain biographies...A carefully

crafted and compelling tragedy.”

—Library Journal

“Dozens of books have been written about Cobain and his

band, most of them ridiculously lurid or worshipful or

uninformed. Heavier Than Heaven is the best, by far...

Excellent.”

—The Portland Oregonian

“Insightful, painstakingly researched...A tremendous gift to

those who love Kurt Cobain’s artistry.”

—The Seattle Weekly

“A closely researched, clear-eyed look at the complicated,even mystifying character that was Kurt Cobain.”

—The Associated Press

“Heavier Than Heaven is a book that gives shape and depth to

a story that has so often been related as a series of loadedanecdotes... Heavier Than Heaven is a trove of rigorous

detail.”

—The Boston Phoenix

“Charles R. Cross has cracked the code in the definitive

biography, an all-access pass to Cobain’s heart and

mind....The deepest book about pop’s darkest falling star.”

—Amazon.com

“Exhaustively researched... Unexpectedly vivid. More

riveting and suspenseful than a biography has the right to

be.”

—Blender

“Fascinating. The most vivid account yet. Will enthrall even

the most casual reader.”

—Mojo

“Superbly researched and harrowing. Cross has painstakingly

accumulated a wealth of telling detail.”

—The London Sunday Times

“Leaps to the front of the class....If you can read only one

Kurt Cobain book, Heavier Than Heaven is definitely it.”

—The Montreal Gazette

“A sublime, uncanny portrait. The way Cross recreates

Cobain’s final hours is beautifully written and paced....By

the end of the chapter I had my face in my hands, helpless

against the tears.”

—The Globe and MailDedication

FOR MY FAMILY, FOR CHRISTINA, AND FOR ASHLANDContents

Praise for Heavier Than Heaven

Author’s Note

Prologue: Heavier Than Heaven - New York, New

York: January 12, 1992

Chapter 1: Yelling Loudly at First - Aberdeen,Washington: February 1967–December 1973

Chapter 2: I Hate Mom, I Hate Dad - Aberdeen,Washington: January 1974–June 1979

Chapter 3: Meatball of the Month - Montesano,Washington: July 1979–March 1982

Chapter 4: Prairie Belt Sausage Boy - Aberdeen,Washington: March 1982–March 1983

Chapter 5: The Will of Instinct - Aberdeen,Washington: April 1984–September 1986

Chapter 6: Didn’t Love Him Enough - Aberdeen,Washington: September 1986–March 1987

Chapter 7: Soupy Sales in My Fly - Raymond,Washington: March 1987

Chapter 8: In High School Again - Olympia,Washington: April 1987–May 1988Chapter 9: Too Many Humans - Olympia,Washington: May 1988–February 1989

Chapter 10: Illegal to Rock N’ Roll -

Olympia, Washington: February 1989–September

1989

Chapter 11: Candy, Puppies, Love - London,England: October 1989–May 1990

Chapter 12: Love You So Much - Olympia,Washington: May 1990–December 1990

Chapter 13: The Richard Nixon Library -

Olympia, Washington: November 1990–May 1991

Chapter 14: Burn American Flags - Olympia,Washington: May 1991–September 1991

Chapter 15: Every Time I Swallowed - Seattle,Washington: September 1991–October 1991

Chapter 16: Brush Your Teeth. - Seattle,Washington: October 1991–January 1992

Chapter 17: Little Monster Inside - Los

Angeles, California: January 1992–August 1992

Chapter 18: Rosewater, Diaper Smell - Los

Angeles, California: August 1992–September

1992

Chapter 19: That Legendary Divorce - Seattle,Washington: September 1992–January 1993

Chapter 20: Heart-Shaped Coffin - Seattle,Washington: January 1993–August 1993

Chapter 21: A Reason to Smile - Seattle,Washington: August 1993–November 1993Chapter 22: Cobain’s Disease - Seattle,Washington: November 1993–March 1994

Chapter 23: Like Hamlet - Seattle, Washington:

March 1994

Chapter 24: Angel’s Hair - Los Angeles,California–Seattle, Washington: March 30–

April 6, 1994

Epilogue: A Leonard Cohen Afterworld - Seattle,Washington: April 1994–May 1999

Source Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

Picture Section

About the Author

CopyrightAuthor’s Note

Less than a mile from my home sits a building that can send a

graveyard chill up my spine as easily as an Alfred Hitchcock

film. The gray one-story structure is surrounded by a tall

chain-link fence, unusual security in a middle-class

neighborhood of sandwich shops and apartments. Three

businesses are behind the fencing: a hair salon; a State Farm

Insurance office; and “Stan Baker, Shooting Sports.” It was

in this third business where on March 30, 1994, Kurt Cobain

and a friend purchased a Remington shotgun. The owner later

told a newspaper he was unsure why anyone would be buying

such a gun when it wasn’t “hunting season.”

Every time I drive by Stan Baker’s I feel as if I’ve

witnessed a particularly horrific roadside accident, and in a

way I have. The events that followed Kurt’s gun shop

purchase leave me with both a deep unease and the desire to

make inquiries that I know by their very nature are

unknowable. They are questions concerning spirituality, the

role of madness in artistic genius, the ravages of drug abuse

on a soul, and the desire to understand the chasm between the

inner and outer man. These questions are all too real to any

family touched by addiction, depression, or suicide. For

families en-shrouded by such darkness—which includes mine—

this need to ask questions that can’t be answered is its own

kind of haunting.

Those mysteries fueled this book but in a way its genesis

began years before during my youth in a small Washington town

where monthly packages from the Columbia Record and Tape Club

offered me rock n’ roll salvation from circumstance.

Inspired in part by those mail-order albums, I left that

rural landscape to become a writer and magazine editor inSeattle. Across the state and a few years later, Kurt Cobain

found a similar transcendence through the same record club

and he turned that interest into a career as a musician. Our

paths would intersect in 1989 when my magazine did the first

cover story on Nirvana.

It was easy to love Nirvana because no matter how great

their fame and glory they always seemed like underdogs, and

the same could be said for Kurt. He began his artistic life

in a double-wide trailer copying Norman Rockwell

illustrations and went on to develop a story-telling gift

that would infuse his music with a special beauty. As a rock

star, he always seemed a misfit, but I cherished the way he

combined adolescent humor with old man crustiness. Seeing him

around Seattle—impossible to miss with his ridiculous cap

with flaps over his ears—he was a character in an industry

with few true characters.

There were many times writing this book when that humor

seemed the only beacon of light in a Sisyphean task. Heavier

Than Heaven encompassed four years of research, 400

interviews, numerous file cabinets of documents, hundreds of

musical recordings, many sleepless nights, and miles and

miles driving between Seattle and Aberdeen. The research took

me places—both emotional and physical—that I thought I’d

never go. There were moments of great elation, as when I

first heard the unreleased “You Know You’re Right,” a song

I’d argue ranks with Kurt’s best. Yet for every joyful

discovery, there were times of almost unbearable grief, as

when I held Kurt’s suicide note in my hand, observing it was

stored in a heart-shaped box next to a keepsake lock of his

blond hair.

My goal with Heavier Than Heaven was to honor Kurt Cobain

by telling the story of his life—of that hair and that note

—without judgment. That approach was only possible because

of the generous assistance of Kurt’s closest friends, his

family, and his bandmates. Nearly everyone I desired to

interview eventually shared their memories—the only

exceptions were a few individuals with plans to write theirown histories, and I wish them the best in those efforts.

Kurt’s life was a complicated puzzle, all the more complex

because he kept so many parts hidden, and that

compartmentalization was both an end result of addiction, and

a breeding ground for it. At times I imagined I was studying

a spy, a skilled double agent, who had mastered the art of

making sure that no one person knew all the details of his

life.

A friend of mine, herself a recovering drug addict, once

described what she called the “no talk” rule of families

like hers. “We grew up in households,” she said, “where we

were told: ‘don’t ask, don’t talk, and don’t tell.’ It

was a code of secrecy, and out of those secrets and lies a

powerful shame overtook me.” This book is for all those with

the courage to tell the truth, to ask painful questions, and

to break free of the shadows of the past.

—Charles R. Cross

Seattle, Washington,April 2001Prologue: HEAVIER THAN HEAVEN

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

JANUARY 12, 1992

Heavier Than Heaven

—A slogan used by British concert promoters to describe

Nirvana’s 1989 tour with the band Tad. It summed up both

Nirvana’s “heavy” sound and the heft of 300-pound Tad

Doyle.

The first time he saw heaven came exactly six hours and

fifty-seven minutes after the very moment an entire

generation fell in love with him. It was, remarkably, his

first death, and only the earliest of many little deaths that

would follow. For the generation smitten with him, it was an

impassioned, powerful, and binding devotion—the kind of love

that even as it begins you know is preordained to break your

heart and to end like a Greek tragedy.

It was January 12, 1992, a clear but chilly Sunday morning.

The temperature in New York City would eventually rise to 44

degrees, but at 7 a.m., in a small suite of the Omni Hotel,it was near freezing. A window had been left open to air out

the stench of cigarettes, and the Manhattan morning had

stolen all warmth. The room itself looked like a tempest had

engulfed it: Scattered on the floor, with the randomness of a

blind man’s rummage sale, were clumps of dresses, shirts,and shoes. Toward the suite’s double doors stood a half

dozen serving trays covered with the remnants of several days

of room service meals. Half-eaten rolls and rancid slices of

cheese littered the tray tops, and a handful of fruit flies

hovered over some wilted lettuce. This was not the typical

condition of a four-star hotel room—it was the consequence

of someone warning housekeeping to stay out of the room. Theyhad altered a “Do Not Disturb” sign to read, “Do Not EVER

Disturb! We’re Fucking!”

There was no intercourse this morning. Asleep in the king-

size bed was 26-year-old Courtney Love. She was wearing an

antique Victorian slip, and her long blond hair spread out

over the sheet like the tresses of a character in a fairy

tale. Next to her was a deep impression in the bedding, where

a person had recently lain. Like the opening scene of a film

noir, there was a dead body in the room.

“I woke up at 7 a.m. and he wasn’t in the bed,”

remembered Love. “I’ve never been so scared.”

Missing from the bed was 24-year-old Kurt Cobain. Less than

seven hours earlier, Kurt and his band Nirvana had been the

musical act on “Saturday Night Live.” Their appearance on

the program would prove to be a watershed moment in the

history of rockn’ roll: the first time a grunge band had

received live national television exposure. It was the same

weekend that Nirvana’s major label debut, Nevermind, knocked

Michael Jackson out of the No. 1 spot on the Billboard

charts, becoming the best-selling album in the nation. While

it wasn’t exactly overnight success—the band had been

together four years—the manner in which Nirvana had taken

the music industry by surprise was unparalleled. Virtually

unknown a year before, Nirvana stormed the charts with their

“Smells Like Teen Spirit,” which became 1991’s most

recognizable song, its opening guitar riff signifying the

true beginning of nineties rock.

And there had never quite been a rock star like Kurt

Cobain. He was more an anti-star than a celebrity, refusing

to take a limo to NBC and bringing a thrift-store sensibility

to everything he did. For “Saturday Night Live” he wore the

same clothes from the previous two days: a pair of Converse

tennis shoes, jeans with big holes in the knees, a T-shirt

advertising an obscure band, and a Mister Rogers–style

cardigan sweater. He hadn’t washed his hair for a week, but

had dyed it with strawberry Kool-Aid, which made his blond

locks look like they’d been matted with dried blood. Neverbefore in the history of live television had a performer put

so little care into his appearance or hygiene, or so it

seemed.

Kurt was a complicated, contradictory misanthrope, and what

at times appeared to be an accidental revolution showed hints

of careful orchestration. He professed in many interviews to

detest the exposure he’d gotten on MTV, yet he repeatedly

called his managers to complain that the network didn’t play

his videos nearly enough. He obsessively— and compulsively—

planned every musical or career direction, writing ideas out

in his journals years before he executed them, yet when he

was bestowed the honors he had sought, he acted as if it were

an inconvenience to get out of bed. He was a man of imposing

will, yet equally driven by a powerful self-hatred. Even

those who knew him best felt they knew him hardly at all—the

happenings of that Sunday morning would attest to that.

After finishing “Saturday Night Live” and skipping the

cast party, explaining it was “not his style,” Kurt had

given a two-hour interview to a radio journalist, which

finished at four in the morning. His working day was finally

over, and by any standard it had been exceptionally

successful: He’d headlined “Saturday Night Live,” had seen

his album hit No. 1, and “Weird Al” Yankovic had asked

permission to do a parody of “Teen Spirit.” These events,taken together, surely marked the apogee of his short career,the kind of recognition most performers only dream of, and

that Kurt himself had fantasized about as a teenager.

Growing up in a small town in southwestern Washington

state, Kurt had never missed an episode of “Saturday Night

Live,” and had bragged to his friends in junior high school

that one day he’d be a star. A decade later, he was the most

celebrated figure in music. After just his second album he

was being hailed as the greatest songwriter of his

generation; only two years before, he had been turned down

for a job cleaning dog kennels.

But in the predawn hours, Kurt felt neither vindication nor

an urge to celebrate; if anything, the attention hadincreased his usual malaise. He felt physically ill,suffering from what he described as “recurrent burning

nauseous pain” in his stomach, made worse by stress. Fame

and success only seemed to make him feel worse. Kurt and his

fiancée, Courtney Love, were the most talked-about couple in

rock n’ roll, though some of that talk was about drug

abuse. Kurt had always believed that recognition for his

talent would cure the many emotional pains that marked his

early life; becoming successful had proven the folly of this

and increased the shame he felt that his booming popularity

coincided with an escalating drug habit.

In his hotel room, in the early hours of the morning, Kurt

had taken a small plastic baggie of China white heroin,prepared it for a syringe, and injected it into his arm. This

in itself was not unusual, since Kurt had been doing heroin

regularly for several months, with Love joining him in the

two months they’d been a couple. But this particular night,as Courtney slept, Kurt had recklessly—or intentionally—

used far more heroin than was safe. The overdose turned his

skin an aqua-green hue, stopped his breathing, and made his

muscles as stiff as coaxial cable. He slipped off the bed and

landed facedown in a pile of clothes, looking like a corpse

haphazardly discarded by a serial killer.

“It wasn’t that he OD’d,” Love recalled. “It was that

he was DEAD. If I hadn’t woken up at seven...I don’t know,maybe I sensed it. It was so fucked. It was sick and

psycho.” Love frantically began a resuscitation effort that

would eventually become commonplace for her: She threw cold

water on her fiancé and punched him in the solar plexus so as

to make his lungs begin to move air. When her first actions

didn’t get a response, she went through the cycle again like

a determined paramedic working on a heart-attack victim.

Finally, after several minutes of effort, Courtney heard a

gasp, signifying Kurt was breathing once again. She continued

to revive him by splashing water on his face and moving his

limbs. Within a few minutes, he was sitting up, talking, and

though still very stoned, wearing a self-possessed smirk,almost as if he were proud of his feat. It was his first

near-death overdose. It had come on the very day he had

become a star.

In the course of one singular day, Kurt had been born in

the public eye, died in the privacy of his own darkness, and

was resurrected by a force of love. It was an extraordinary

feat, implausible, and almost impossible, but the same could

be said for so much of his outsized life, beginning with

where he’d come from.Chapter 1

YELLING LOUDLY AT FIRST

ABERDEEN, WASHINGTON

FEBRUARY 1967–DECEMBER 1973

He makes his wants known by yelling loudly at first, then

crying if the first technique doesn’t work.

—Excerpt from a report by his aunt on the eighteen-

month-old Kurt Cobain.

Kurt Donald Cobain was born on the twentieth of February,1967, in a hospital on a hill overlooking Aberdeen,Washington. His parents lived in neighboring Hoquiam, but it

was appropriate that Aberdeen stand as Kurt’s birthplace—he

would spend three quarters of his life within ten miles of

the hospital and would be forever profoundly connected to

this landscape.

Anyone looking out from Grays Harbor Community Hospital

that rainy Monday would have seen a land of harsh beauty,where forests, mountains, rivers, and a mighty ocean

intersected in a magnificent vista. Tree-covered hills

surrounded the intersection of three rivers, which fed into

the nearby Pacific Ocean. In the center of it all was

Aberdeen, the largest city in Grays Harbor County, with a

population of 19,000. Immediately to the west was smaller

Hoquiam, where Kurt’s parents, Don and Wendy, lived in a

tiny bungalow. And south across the Chehalis River was

Cosmopolis, where his mother’s family, the Fradenburgs, were

from. On a day when it wasn’t raining—which was a rare day

in a region that got over 80 inches of precipitation a year—

one could see the nine miles to Montesano, where Kurt’s

grandfather Leland Cobain grew up. It was a small enoughworld, with so few degrees of separation that Kurt would

eventually become Aberdeen’s most famous product.

The view from the three-story hospital was dominated by the

sixth busiest working harbor on the West Coast. There were so

many pieces of timber floating in the Chehalis that you could

imagine using them to walk across the two-mile mouth. To the

east was Aberdeen’s downtown, where merchants complained

that the constant rumbling of logging trucks scared away

shoppers. It was a city at work, and that work almost

entirely depended on turning Douglas fir trees from the

surrounding hills into commerce. Aberdeen was home to 37

different lumber, pulp, shingle, or saw mills—their

smokestacks dwarfed the town’s tallest building, which had

only seven stories. Directly down the hill from the hospital

was the gigantic Rayonier Mill smokestack, the biggest tower

of all, which stretched 150 feet toward the heavens and

spewed forth an unending celestial cloud of wood-pulp

effluence.

Yet as Aberdeen buzzed with motion, at the time of Kurt’s

birth its economy was slowly contracting. The county was one

of the few in the state with a declining population, as the

unemployed tried their luck elsewhere. The timber industry

had begun to suffer the consequences of offshore competition

and over-logging. The landscape already showed marked signs

of such overuse: There were swaths of clear-cut forests

outside of town, now simply a reminder of early settlers who

had “tried to cut it all,” as per the title of a local

history book. Unemployment exacted a darker social price on

the community in the form of increasing alcoholism, domestic

violence, and suicide. There were 27 taverns in 1967, and the

downtown core included many abandoned buildings, some of

which had been brothels before they were closed in the late

fifties. The city was so infamous for whorehouses that in

1952 Look magazine called it “one of the hot spots in

America’s battle against sin.”

Yet the urban blight of downtown Aberdeen was paired with a

close-knit social community where neighbors helped neighbors,parents were involved in schools, and family ties remained

strong among a diverse immigrant population. Churches

outnumbered taverns, and it was a place, like much of small-

town America in the mid-sixties, where kids on bikes were

given free rein in their neighborhoods. The entire city would

become Kurt’s backyard as he grew up.

Like most first births, Kurt’s was a celebrated arrival,both for his parents and for the larger family. He had six

aunts and uncles on his mother’s side; two uncles on his

father’s side; and he was the first grandchild for both

family trees. These were large families, and when his mother

went to print up birth announcements, she used up 50 before

she was through the immediate relations. A line in the

Aberdeen Daily World’s birth column on February 23 noted

Kurt’s arrival to the rest of the world: “To Mr. and Mrs.

Donald Cobain, 2830? Aberdeen Avenue, Hoquiam, February 20,at Community Hospital, a son.”

Kurt weighed seven pounds, seven and one-half ounces at

birth, and his hair and complexion were dark. Within five

months, his baby hair would turn blond, and his coloring

would turn fair. His father’s family had French and Irish

roots—they had immigrated from Skey Townland in County

Tyrone, Ireland, in 1875—and Kurt inherited his angular chin

from this side. From the Fradenburgs on his mother’s side—

who were German, Irish, and English—Kurt gained rosy cheeks

and blond locks. But by far his most striking feature was his

remarkable azure eyes; even nurses in the hospital commented

on their beauty.

It was the sixties, with a war raging in Vietnam, but apart

from the occasional news dispatch, Aberdeen felt more like

1950s America. The day Kurt was born, the Aberdeen Daily

World contrasted the big news of an American victory at Quang

Ngai City with local reports on the size of the timber

harvest and ads from JCPenney, where a Washington’s Birthday

sale featured 2.48 flannel shirts. Who’s Afraid of Virginia

Woolf? had received thirteen Academy Award nominations in LosAngeles that afternoon, but the Aberdeen drive-in was playing

Girls on the Beach.

Kurt’s 21-year-old father, Don, worked at the Chevron

station in Hoquiam as a mechanic. Don was handsome and

athletic, but with his flattop haircut and Buddy Holly–style

glasses he had a geekiness about him. Kurt’s 19-year-old

mother, Wendy, in contrast, was a classic beauty who looked

and dressed a bit like Marcia Brady. They had met in high

school, where Wendy had the nickname “Breeze.” The previous

June, just weeks after her high-school graduation, Wendy had

become pregnant. Don borrowed his father’s sedan and

invented an excuse so the two could travel to Idaho and marry

without parental consent.

At the time of Kurt’s birth the young couple were living

in a tiny house in the backyard of another home in Hoquiam.

Don worked long hours at the service station while Wendy took

care of the baby. Kurt slept in a white wicker bassinet with

a bright yellow bow on top. Money was tight, but a few weeks

after the birth they managed to scrape up enough to leave the

tiny house and move into a larger one at 2830 Aberdeen

Avenue. “The rent,” remembered Don, “was only an extra

five dollars a month, but in those times, five dollars was a

lot of money.”

If there was a portent of trouble in the household, it

began over finances. Though Don had been appointed “lead

man” at the Chevron in early 1968, his salary was only

6,000 a year. Most of their neighbors and friends worked in

the timber industry, where jobs were physically demanding—

one study described the profession as “more deadly than

war”—but with higher wages in return. The Cobains struggled

to stay within a budget, yet when it came to Kurt, they made

sure he was well-dressed, and even sprang for professional

photos. In one series of pictures from this era, Kurt is

wearing a white dress shirt, black tie, and a gray suit,looking like Little Lord Fauntleroy—he still has his baby

fat and chubby, full cheeks. In another, he wears a matchingblue vest and suit top, and a hat more suited to Phillip

Marlowe than a year-and-a-half-old boy.

In May 1968, when Kurt was fifteen months old, Wendy’s

fourteen-year-old sister Mari wrote a paper about her nephew

for her home economics class. “His mother takes care of him

most of the time,” Mari wrote. “[She] shows her affection

by holding him, giving him praise when he deserves it, and by

taking part in many of his activities. He responds to his

father in that when he sees his father, he smiles, and he

likes his dad to hold him. He makes his wants known by

yelling loudly at first, then crying if the first technique

doesn’t work.” Mari recorded that his favorite game was

peekaboo, his first tooth appeared at eight months, and his

first dozen words were, “coco, momma, dadda, ball, toast,bye-bye, hi, baby, me, love, hot dog, and kittie.”

Mari listed his favorite toys as a harmonica, a drum, a

basketball, cars, trucks, blocks, a pounding block, a toy TV,and a telephone. Of Kurt’s daily routine, she wrote that

“his reaction to sleep is that he cries when he is laid down

to do so. He is so interested in the family that he doesn’t

want to leave them.” His aunt concluded: “He is a happy,smiling baby and his personality is developing as it is

because of the attention and love he is receiving.”

Wendy was a mindful mother, reading books on learning,buying flash cards, and, aided by her brothers and sisters,making sure Kurt got proper care. The entire extended family

joined in the celebration of this child, and Kurt flourished

with the attention. “I can’t even put into words the joy

and the life that Kurt brought into our family,” remembered

Mari. “He was this little human being who was so bubbly. He

had charisma even as a baby. He was funny, and he was

bright.” Kurt was smart enough that when his aunt couldn’t

figure out how to lower his crib, the one-and-a-half-year-old

simply did it himself. Wendy was so enamored of her son’s

antics, she rented a Super-8 camera and shot movies of him—

an expense the family could ill afford. One film shows ahappy, smiling little boy cutting his second-year birthday

cake and looking like the center of his parents’ universe.

By his second Christmas, Kurt was already showing an

interest in music. The Fradenburgs were a musical family—

Wendy’s older brother Chuck was in a band called the

Beachcombers; Mari played guitar; and great-uncle Delbert had

a career as an Irish tenor, even appearing in the movie The

King of Jazz. When the Cobains visited Cosmopolis, Kurt was

fascinated by the family jam sessions. His aunts and uncles

recorded him singing the Beatles’ “Hey Jude,” Arlo

Guthrie’s “Motorcycle Song,” and the theme to “The

Monkees” television show. Kurt enjoyed making up his own

lyrics, even as a toddler. When he was four, upon his return

from a trip to the park with Mari, he sat down at the piano

and crafted a crude song about their adventure. “We went to

the park, we got candy,” went the lyrics. “I was just

amazed,” recalled Mari. “I should have plugged in the tape

recorder—it was probably his first song.”

Not long after he turned two, Kurt created an imaginary

friend he called Boddah. His parents eventually became

concerned about his attachment to this phantom pal, so when

an uncle was sent to Vietnam, Kurt was told that Boddah too

had been drafted. But Kurt didn’t completely buy this story.

When he was three, he was playing with his aunt’s tape

machine, which had been set to “echo.” Kurt heard the echo

and asked, “Is that voice talking to me? Boddah? Boddah?”

In September 1969, when Kurt was two and a half, Don and

Wendy bought their first home at 1210 East First Street in

Aberdeen. It was a two-story, 1,000-square-foot house with a

yard and a garage. They paid 7,950 for it. The 1923-era

dwelling was located in a neighborhood occasionally given the

derogatory nickname “felony flats.” North of the Cobain

house was the Wishkah River, which frequently flooded, and to

the southeast was the wooded bluff locals called “Think of

Me Hill”—at the turn of the century it had sported an

advertisement for Think of Me cigars.It was a middle-class house in a middle-class neighborhood,which Kurt would later describe as “white trash posing as

middle-class.” The first floor contained the living room,dining room, kitchen, and Wendy and Don’s bedroom. The

upstairs had three rooms: a small playroom and two bedrooms,one of which became Kurt’s. The other was planned for

Kurt’s sibling—that month Wendy had learned she was

pregnant again.

Kurt was three when his sister Kimberly was born. She

looked, even as an infant, remarkably like her brother, with

the same mesmerizing blue eyes and light blond hair. When

Kimberly was brought home from the hospital, Kurt insisted on

carrying her into the house. “He loved her so much,”

remembered his father. “And at first they were darling

together.” Their three-year age difference was ideal because

her care became one of his main topics of conversation. This

marked the beginning of a personality trait that would stick

with Kurt for the rest of his life—he was sensitive to the

needs and pains of others, at times overly so.

Having two children changed the dynamic of the Cobain

household, and what little leisure time they had was taken up

by visits with family or Don’s interest in intramural

sports. Don was in a basketball league in winter and played

on a baseball team in summer, and much of their social life

involved going to games or post-game events. Through sports,the Cobains met and befriended Rod and Dres Herling. “They

were good family people, and they did lots of things with

their kids,” Rod Herling recalled. Compared with other

Americans going through the sixties, they were also notably

square: At the time no one in their social circle smoked pot,and Don and Wendy rarely drank.

One summer evening the Herlings were at the Cobains’

playing cards, when Don came into the living room and

announced, “I have a rat.” Rats were common in Aberdeen

because of the low elevation and abundance of water. Don

began to fashion a crude spear by attaching a butcher knife

to a broom handle. This drew the interest of five-year-oldKurt, who followed his father to the garage, where the rodent

was in a trash can. Don told Kurt to stand back, but this was

impossible for such a curious child and the boy kept inching

closer until he was holding his father’s pant leg. The plan

was for Rod Herling to lift the lid of the can, whereupon Don

would use his spear to stab the rat. Herling lifted, Don

threw the broomstick but missed the rat, and the spear stuck

into the floor. As Don tried in vain to pull the broom out,the rat—at a calm and bemused pace—crawled up the

broomstick, scurried over Don’s shoulder and down to the

ground, and ran over Kurt’s feet as he exited the garage. It

happened in a split second, but the combination of the look

on Don’s face and the size of Kurt’s eyes made everyone

howl with laughter. They laughed for hours over this

incident, and it would become a piece of family folklore:

“Hey, do you remember that time Dad tried to spear the

rat?” No one laughed harder than Kurt, but as a five-year-

old he laughed at everything. It was a beautiful laugh, like

the sound of a baby being tickled, and it was a constant

refrain.

In September 1972, Kurt began kindergarten at Robert Gray

Elementary, three blocks north of his house. Wendy walked him

to school the first day, but after that he was on his own;

the neighborhood around First Street had become his turf. He

was well-known to his teachers as a precocious, inquisitive

pupil with a Snoopy lunchbox. On his report card that year

his teacher wrote “real good student.” He was not shy. When

a bear cub was brought in for show-and-tell, Kurt was one of

the only kids who posed with it for photos.

The subject he excelled in the most was art. At the age of

five it was already clear he had exceptional artistic skills:

He was creating paintings that looked realistic. Tony

Hirschman met Kurt in kindergarten and was impressed by his

classmate’s ability: “He could draw anything. Once we were

looking at pictures of werewolves, and he drew one that

looked just like the photo.” A series Kurt did that yeardepicted Aqua-man, the Creature From the Black Lagoon, Mickey

Mouse, and Pluto. Every holiday or birthday his family gave

him supplies, and his room began to take on the appearance of

an art studio.

Kurt was encouraged in art by his paternal grandmother,Iris Cobain. She was a collector of Norman Rockwell

memorabilia in the form of Franklin Mint plates with Saturday

Evening Post illustrations on them. She herself recreated

many of Rockwell’s images in needlepoint—and his most

famous painting, “Freedom From Want,” showing the

quintessential American Thanksgiving dinner, hung on the wall

of her doublewide trailer in Montesano. Iris even convinced

Kurt to join her in a favorite craft: using toothpicks to

carve crude reproductions of Rockwell’s images onto the tops

of freshly picked fungi. When these oversized mushrooms would

dry, the toothpick scratchings would remain, like backwoods

scrimshaw.

Iris’s husband and Kurt’s grandfather, Leland Cobain,wasn’t himself artistic—he had driven an asphalt roller,which had cost him much of his hearing—but he did teach Kurt

woodworking. Leland was a gruff and crusty character, and

when his grandson showed off a picture of Mickey Mouse that

he’d drawn (Kurt loved Disney characters), Leland accused

him of tracing it. “I did not,” Kurt said. “You did,too,” Leland responded. Leland gave Kurt a new piece of

paper and a pencil and challenged him: “Here, you draw me

another one and show me how you did it.” The six-year-old

sat down, and without a model drew a near-perfect

illustration of Donald Duck and another of Goofy. He looked

up from the paper with a huge grin, just as pleased at

showing up his grandfather as in creating his beloved duck.

His creativity increasingly extended to music. Though he

never took formal piano lessons, he could pound out a simple

melody by ear. “Even when he was a little kid,” remembered

his sister Kim, “he could sit down and just play something

he’d heard on the radio. He was able to artistically put

whatever he thought onto paper or into music.” To encouragehim, Don and Wendy bought a Mickey Mouse drum set, which Kurt

vigorously pounded every day after school. Though he loved

the plastic drums, he liked the real drums at his Uncle

Chuck’s house better, since he could make more noise with

them. He also enjoyed strapping on Aunt Mari’s guitar, even

though it was so heavy it made his knees buckle. He’d strum

it while inventing songs. That year he bought his first

record, a syrupy single by Terry Jacks called “Seasons in

the Sun.”

He also loved looking through his aunts’ and uncles’

albums. One time, when he was six, he visited Aunt Mari and

was digging through her record collection, looking for a

Beatles album—they were one of his favorites. Kurt suddenly

cried out and ran toward his aunt in a panic. He was holding

a copy of the Beatles’ Yesterday and Today, with the

infamous “Butcher cover,” with artwork showing the band

with pieces of meat on them. “It made me realize how

impressionable he was at that age,” Mari remembered.

He was also sensitive to the increasing strain he saw

between his parents. For the first few years of Kurt’s life,there wasn’t much fighting in the home, but there also

hadn’t been evidence of a great love affair. Like many

couples who married young, Don and Wendy were two people

overwhelmed by circumstance. Their children became the center

of their lives, and what little romance had existed in the

short time they’d had prior to their kids was hard to

rekindle. The financial pressures daunted Don; Wendy was

consumed by caring for two children. They began to argue more

and to yell at each other in front of the children. “You

have no idea how hard I work,” Don screamed at Wendy, who

echoed her husband’s complaint.

Still, for Kurt, there was much joy in his early childhood.

In the summer they’d vacation at a Fradenburg family cabin

at Washaway Beach on the Washington coast. In winter they’d

go sledding. It rarely snowed in Aberdeen, so they would

drive east into the small hills past the logging town of

Porter, and to Fuzzy Top Mountain. Their sledding tripsalways followed a similar pattern: They’d park, pull out a

toboggan for Don and Wendy, a silver saucer for Kim, and

Kurt’s Flexible Flyer, and prepare to slide down the hill.

Kurt would grab his sled, get a running start, and hurl

himself down the hill the way an athlete would commence the

long jump. Once he reached the bottom he would wave at his

parents, the signal he had survived the trip. The rest of the

family would follow, and they would walk back up the hill

together. They’d repeat the cycle again and again for hours,until darkness fell or Kurt dropped from exhaustion. As they

headed toward the car Kurt would make them promise to return

the next weekend. Later, Kurt would recall these times as the

fondest memories of his youth.

When Kurt was six, the family went to a downtown photo

studio and sat for a formal Christmas portrait. In the photo,Wendy sits in the center of the frame with a spotlight behind

her head creating a halo; she rests on an oversized, wooden

high-backed chair, wearing a long white-and-pink-striped

Victorian dress with ruffled cuffs. Around her neck is a

black choker, and her shoulder-length strawberry blond hair

is parted in the middle, not a single strand out of place.

With her perfect posture and the manner in which her wrists

hang over the arms of the chair, she looks like a queen.

Three-year-old Kim sits on her mom’s lap. Dressed in a

long, white dress with black patent leather shoes, she

appears as a miniature version of her mother. She is staring

directly at the camera and has the appearance of a child who

might start crying at any moment.

Don stands behind the chair, close enough to be in the

picture but distracted. His shoulders are slightly stooped

and he wears more of a bemused look than a legitimate smile.

He is wearing a light purple long-sleeved shirt with a four-

inch collar and a gray vest—it’s an outfit that one could

imagine Steve Martin or Dan Aykroyd donning for their “wild

and crazy guys” skit on “Saturday Night Live.” He has a

far-off look in his eyes, as if he is wondering just why hehas been dragged down to the photo studio when he could be

playing ball.

Kurt stands off to the left, in front of his father, a foot

or two away from the chair. He’s wearing two-tone, striped

blue pants with a matching vest and a fire-truck red long-

sleeved shirt a bit too big for him, the sleeves partially

covering his hands. As the true entertainer in the family, he

is not only smiling, but he’s laughing. He looks notably

happy—a little boy having fun on a Saturday with his family.

It is a remarkably good-looking family, and the outward

appearances suggest an all-American pedigree—clean hair,white teeth, and well-pressed clothes so stylized they could

have been ripped out of an early seventies Sears catalog. Yet

a closer look reveals a dynamic that even to the photographer

must have been painfully obvious: It’s a picture of a

family, but not a picture of a marriage. Don and Wendy

aren’t touching, and there is no suggestion of affection

between them; it is as if they’re not even in the same

frame. With Kurt standing in front of Don, and Kim sitting on

Wendy’s lap, one could easily take a pair of scissors and

sever the photograph—and the family—down the middle. You’d

be left with two separate families, each with one adult and

one child, each gender specific—the Victorian dresses on one

side, and the boys with wide collars on the other.Chapter 2

I HATE MOM, I HATE DAD

ABERDEEN, WASHINGTON

JANUARY 1974–JUNE 1979

I hate Mom, I hate Dad.

—From a poem on Kurt’s bedroom wall.

The stress on the family increased in 1974, when Don Cobain

decided to change jobs and enter the timber industry. Don

wasn’t a large man, and he didn’t have much interest in

cutting down 200-foot trees, so he took an office position at

Mayr Brothers. He knew eventually he could make more money in

timber than working at the service station; unfortunately,his first job was entry level, paying 4.10 an hour, even

less than he’d made as a mechanic. He picked up extra money

doing inventory at the mill on weekends, and he’d frequently

take Kurt with him. “He’d ride his little bike around the

yard,” Don recalled. Kurt later would mock his father’s

job, and claim it was hell to accompany Don to work, but at

the time he reveled in being included. Though he spent all of

his adult life trying to argue otherwise, acknowledgment and

attention from his father was critically important for Kurt,and he desired more of it, not less. He would later admit

that his early years within his nuclear family were joyful

memories. “I had a really good childhood,” he told Spin

magazine in 1992, but not without adding, “up until I was

nine.”

Don and Wendy frequently had to borrow money to pay their

bills, one of the main sources of their arguments. Leland and

Iris kept a 20 bill in their kitchen—they joked that it was

a bouncing twenty because each month they’d loan it to theirson for groceries, and immediately after repaying them Don

would borrow it again. “He’d go all around, pay all his

bills, and then he’d come to our house,” remembered Leland.

“He’d pay us our 20, and then he’d say, ‘Hell, I done

pretty good this week. I got 35 or 40 cents left.’ ”

Leland, who never liked Wendy because he perceived her as

acting “better than the Cobains,” remembered the young

family would then head off to the Blue Beacon Drive-In on

Boone Street to spend the change on hamburgers. Though Don

got along well with his father-in-law, Charles Fradenburg—

who drove a road grader for the county—Leland and Wendy

never connected.

Tension between the two came to a head when Leland helped

remodel the house on First Street. He built Don and Wendy a

fake fire-place in the living room and put in new

countertops, but in the process he and Wendy battled

increasingly. Leland finally told his son to make Wendy stop

nagging him or he’d exit and leave the job half finished.

“It was the first time I ever heard Donnie talk back to

her,” Leland recalled. “She was bitching about this and

that, and finally he said, ‘Keep your god damn mouth shut or

he’ll take his tools and go home.’ And she shut her mouth

for once.”

Like his father before him, Don was strict with children.

One of Wendy’s complaints was that her husband expected the

kids to always behave—an impossible standard—and required

Kurt to act like a “little adult.” At times, like all

children, Kurt was a terror. Most of his acting-out incidents

were minor at the time—he’d write on the walls or slam the

door or tease his sister. These behaviors frequently elicited

a spanking, but Don’s more common—and almost daily—

physical punishment was to take two fingers and thump Kurt on

the temple or the chest. It only hurt a little, but the

psychological damage was deep—it made his son fear greater

physical harm and it served to reinforce Don’s dominance.

Kurt began to retreat into the closet in his room. The kindof enclosed, confined spaces that would give others panic

attacks were the very places he sought out as sanctuary.

And there were things worth hiding from: Both parents could

be sarcastic and mocking. When Kurt was immature enough to

believe them, Don and Wendy warned him he’d get a lump of

coal for Christmas if he wasn’t good, particularly if he

fought with his sister. As a prank, they left him pieces of

coal in his stocking. “It was just a joke,” Don remembered.

“We did it every year. He got presents and all that— we

never didn’t give him presents.” The humor, however, was

lost on Kurt, at least as he told the story later in life. He

claimed one year he had been promised a Starsky and Hutch toy

gun, a gift that never came. Instead, he maintained he only

received a lump of neatly wrapped coal. Kurt’s telling was

an exaggeration, but in his inner imagination, he had begun

to put his own spin on the family.

Occasionally, Kim and Kurt got along, and at times they’d

play together. Though Kim never had the artistic talent of

Kurt—and she forever felt the rivalry of having the rest of

the family pay him so much attention—she developed a skill

for imitating voices. She was particularly good at Mickey

Mouse and Donald Duck, and these performances amused Kurt to

no end. Her vocal abilities even gave birth to a new fantasy

for Wendy. “It was my mom’s big dream,” declared Kim,“that Kurt and I would end up at Disneyland, both of us

working there, with him drawing and me doing voices.”

March of 1975 was filled with much joy for eight-year-old

Kurt: He finally visited Disneyland, and he took his first

airplane ride. Leland had retired in 1974, and he and Iris

wintered that year in Arizona. Don and Wendy drove Kurt to

Seattle, put him on a plane, and Leland met the boy in Yuma,before they headed for Southern California. In a mad two-day

period, they visited Disneyland, Knotts Berry Farm, and

Universal Studios. Kurt was enthralled and insisted they go

through Disneyland’s “Pirates of the Caribbean” ride three

times. At Knotts Berry Farm, he braved the giant rollercoaster, but when he departed the ride, his face was white as

a ghost. When Leland said, “Had enough?” the color rushed

back and he rode the coaster yet again. On the tour of

Universal Studios, Kurt leaned out of the train in front of

the Jaws shark, spurring a guard to yell at his grandparents,“You better pull that little towheaded boy back or his head

will get bitten off.” Kurt defied the order and snapped a

picture of the mouth of the shark as it came inches away from

his camera. Later that day, driving on the freeway, Kurt fell

asleep in the backseat, which was the only reason his

grandparents were able to sneak by Magic Mountain without him

insisting they visit that as well.

Of all his relatives, Kurt was closest to his grandmother

Iris; they shared both an interest in art and, at times, a

certain sadness. “They adored each other,” remembered Kim.

“I think he intuitively knew the hell she’d been through.”

Both Iris and Leland had difficult upbringings, each scarred

by poverty and the early deaths of their fathers on the job.

Iris’s father had been killed by poisonous fumes at the

Rayonier Pulp Mill; Leland’s dad, who was a county sheriff,died when his gun accidentally discharged. Leland was fifteen

at the time of his father’s death. He joined the Marines and

was sent to Guadalcanal, but after he beat up an officer he

was committed to the hospital for a psychiatric evaluation.

He married Iris after his discharge, but struggled with drink

and anger, especially after their third son, Michael, was

born retarded and died in an institution at age six. “On

Friday night he’d get paid and come home drunk,” recalled

Don. “He used to beat my mom. He’d beat me. He beat my

grandma, and he beat Grandma’s boyfriend. But that’s the

way it was in those days.” By the time of Kurt’s youth,Leland had softened and his most serious weapon was foul

language.

When Leland and Iris weren’t available, one of the various

Fradenburg siblings would baby-sit—three of Kurt’s aunts

lived within four blocks. Don’s younger brother Gary was

also given child-care duties a few times, and one occasionmarked Kurt’s first trip back to the hospital. “I broke his

right arm,” Gary recalled. “I was on my back and he was on

my feet, and I was shooting him up in the air with my feet.”

Kurt was a very active child, and with all the running around

he did, relatives were surprised he didn’t break more limbs.

Kurt’s broken arm healed and the injury didn’t seem to

stop him from playing sports. Don encouraged his son to play

baseball almost as soon as he could walk, and provided him

with all the balls, bats, and mitts that a young boy needed.

As a toddler, Kurt found the bats more useful as percussion

instruments, but eventually he began to participate in

athletics, beginning in the neighborhood, and then in

organized play. At seven, he was on his first Little League

team. His dad was the coach. “He wasn’t the best player on

the team, but he wasn’t bad,” Gary Cobain recalled. “He

didn’t really want to play, I thought, mentally. I think he

did it because of his dad.”

Baseball was an example of Kurt seeking Don’s approval.

“Kurt and my dad got along well when he was young,”

remembered Kim, “but Kurt wasn’t anything like how Dad was

planning on Kurt turning out.”

Both Don and Wendy were facing the conflict between the

idealized child and the real child. Since both had unmet

needs left from their own early years, Kurt’s birth brought

out all their personal expectations. Don wanted the

fatherson relationship he never had with Leland, and he

thought participating in sports together would provide that

bond. And though Kurt liked sports, particularly when his

father wasn’t around, he intuitively connected his father’s

love with this activity, something that would mark him for

life. His reaction was to participate, but to do so under

protest.

When Kurt was in second grade, his parents and teacher

decided his endless energy might have a larger medical root.

Kurt’s pediatrician was consulted and Red Dye Number Two was

removed from his diet. When there was no improvement, his

parents limited Kurt’s sugar in-take. Finally, his doctorprescribed Ritalin, which Kurt took for a period of three

months. “He was hyperactive,” Kim recalled. “He was

bouncing off the walls, particularly if you got any sugar in

him.”

Other relatives suggest Kurt may have suffered from

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Mari

remembered visiting the Cobain house and finding Kurt running

around the neighborhood, banging on a marching drum and

yelling at the top of his lungs. Mari went inside and asked

her sister, “Just what on earth is he doing?” “I don’t

know,” was Wendy’s reply. “I don’t know what to do to get

him to stop—I’ve tried everything.” At the time, Wendy

presumed it was Kurt’s way of burning off his excess of

boyish energy.

The decision to give Kurt Ritalin was, even in 1974, a

controversial one, with some scientists arguing it creates a

Pavlovian response in children and increases the likelihood

of addictive behavior later in life; others believe that if

children aren’t treated for hyperactivity, they may later

self-medicate with illegal drugs. Each member of the Cobain

family had a different opinion on Kurt’s diagnosis and

whether the short course of treatment helped or harmed him,but Kurt’s own opinion, as he later told Courtney Love, was

that the drug was significant. Love, who herself was

prescribed Ritalin as a child, said the two discussed this

issue frequently. “When you’re a kid and you get this drug

that makes you feel that feeling, where else are you going to

turn when you’re an adult?” Love asked. “It was euphoric

when you were a child—isn’t that memory going to stick with

you?”

In February 1976, just a week after Kurt’s ninth birthday,Wendy informed Don she wanted a divorce. She announced this

one weekday night and stormed off in her Camaro, leaving Don

to do the explaining to the children, something at which he

didn’t excel. Though Don and Wendy’s marital conflicts had

increased during the last half of 1974, her declaration tookDon by surprise, as it did the rest of the family. Don went

into a state of denial and moved inward, a behavior that

would be mirrored years later by his son in times of crisis.

Wendy had always been a strong personality and prone to

occasional bouts of rage, yet Don was shocked she wanted to

break up the family unit. Her main complaint was that he was

unceasingly involved in sports—he was a referee and a coach,in addition to playing on a couple of teams. “In my mind, I

didn’t believe it was going to happen,” Don recalled.

“Divorce wasn’t so common then. I didn’t want it to

happen, either. She just wanted out.”

On March 1 it was Don who moved out and took a room in

Hoquiam. He expected Wendy’s anger would subside and their

marriage would survive, so he rented by the week. To Don, the

family represented a huge part of his identity, and his role

as a dad marked one of the first times in his life he felt

needed. “He was crushed by the idea of divorce,” remembered

Stan Targus, Don’s best friend. The split was complicated

because Wendy’s family adored Don, particularly her sister

Janis and husband Clark, who lived near the Cobains. A few of

Wendy’s siblings quietly wondered how she would survive

financially without Don.

On March 29 Don was served with a summons and a “Petition

for Dissolution of Marriage.” A slew of legal documents

would follow; Don would frequently fail to respond, hoping

against hope Wendy would change her mind. On July 9 he was

held in default for not responding to Wendy’s petitions. On

that same day, a final settlement was granted awarding the

house to Wendy but giving Don a lien of 6,500, due whenever

the home was sold, Wendy remarried, or Kim turned eighteen.

Don was granted his 1965 Ford half-ton pickup truck; Wendy

was allowed to keep the family 1968 Camaro.

Custody of the children was awarded to Wendy, but Don was

charged with paying 150 a month per child in support, plus

their medical and dental expenses, and given “reasonable

visitation” rights. This ......

“The narrative moves like the best Nirvana anthems. Smells

like the real deal.”

—Time

“Until someone writes a book that is more daring in its

psychological and social analysis—and as thorough in its

reporting—Heavier Than Heaven will be the place to start the

dark journey into Cobain’s claustrophobic inner world.”

—Rolling Stone

“What emerges...is the life story of someone who never grew

up, someone whose maturation was half done before he was

twenty-one, someone who extracted art from a perpetual

adolescence that was over much too soon.”

—The New Yorker

“The results of Cross’ assiduous reporting show through in

every chapter. A remarkable portrait.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“One of the most moving and revealing books ever written

about a rock star. An invaluable look at the life of a

troubled artist.”

—Los Angeles Times

“In his early teens, Cobain told a friend, ‘I’m going to

be a superstar musician, kill myself and go out in a flame of

glory.’ This well-reported book... provides the most

grounded account of how Cobain, not too many years later, did

just that.”—The New York Times Book Review

“The biography that the most important rocker of his

generation has always deserved: exhaustively researched, full

of insight into the ‘real’ Cobain as opposed to the

manipulated media image, and written in a clear and

compelling... voice.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“A cautionary tale of a talented, lucky musician who became

fatally confused about whether fame was a reward or a death

sentence.”

—People

“No other book on Kurt Cobain matches Heavier Than Heaven

for research, accuracy and insider scoops.”

—The New York Post

“By keeping a steady eye on the facts, Cross mostly pierces

the rumors, hype and conspiracy theories that have long

confounded Nirvana’s place in history...At last, perhaps,Cobain’s ghost can find some peace.”

—The Miami Herald

“Charles R. Cross takes readers deeper into the life of the

brilliant, troubled Kurt Cobain than anyone thought possible.

The result is more than just an excellent book... Cross helps

reset the standards of what biographies—not just rock bios—

should be.”

—The Rocky Mountain News

“Shakes up the prevailing conceptions of Cobain...A

compelling biography.”

—Biography

“A fascinating, if sometimes frightful, read, a full-scale

work that manages to be respectful of Cobain’s unlikelytriumphs from poverty and also critical of his stunning

excesses.”

—The Seattle Post-Intelligencer

“A standout among rock bios and deserves its place in pop-

culture collections.”

—Booklist

“Cross treats the strange, unhappy life of musician Kurt

Cobain with intelligence and an insider’s perceptiveness.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A thorough, cogent look at Kurt Cobain...No other book

matches Heavier Than Heaven for research, accuracy, and

insider scoops.”

—The Seattle Times

“Cross transcends the other Cobain biographies...A carefully

crafted and compelling tragedy.”

—Library Journal

“Dozens of books have been written about Cobain and his

band, most of them ridiculously lurid or worshipful or

uninformed. Heavier Than Heaven is the best, by far...

Excellent.”

—The Portland Oregonian

“Insightful, painstakingly researched...A tremendous gift to

those who love Kurt Cobain’s artistry.”

—The Seattle Weekly

“A closely researched, clear-eyed look at the complicated,even mystifying character that was Kurt Cobain.”

—The Associated Press

“Heavier Than Heaven is a book that gives shape and depth to

a story that has so often been related as a series of loadedanecdotes... Heavier Than Heaven is a trove of rigorous

detail.”

—The Boston Phoenix

“Charles R. Cross has cracked the code in the definitive

biography, an all-access pass to Cobain’s heart and

mind....The deepest book about pop’s darkest falling star.”

—Amazon.com

“Exhaustively researched... Unexpectedly vivid. More

riveting and suspenseful than a biography has the right to

be.”

—Blender

“Fascinating. The most vivid account yet. Will enthrall even

the most casual reader.”

—Mojo

“Superbly researched and harrowing. Cross has painstakingly

accumulated a wealth of telling detail.”

—The London Sunday Times

“Leaps to the front of the class....If you can read only one

Kurt Cobain book, Heavier Than Heaven is definitely it.”

—The Montreal Gazette

“A sublime, uncanny portrait. The way Cross recreates

Cobain’s final hours is beautifully written and paced....By

the end of the chapter I had my face in my hands, helpless

against the tears.”

—The Globe and MailDedication

FOR MY FAMILY, FOR CHRISTINA, AND FOR ASHLANDContents

Praise for Heavier Than Heaven

Author’s Note

Prologue: Heavier Than Heaven - New York, New

York: January 12, 1992

Chapter 1: Yelling Loudly at First - Aberdeen,Washington: February 1967–December 1973

Chapter 2: I Hate Mom, I Hate Dad - Aberdeen,Washington: January 1974–June 1979

Chapter 3: Meatball of the Month - Montesano,Washington: July 1979–March 1982

Chapter 4: Prairie Belt Sausage Boy - Aberdeen,Washington: March 1982–March 1983

Chapter 5: The Will of Instinct - Aberdeen,Washington: April 1984–September 1986

Chapter 6: Didn’t Love Him Enough - Aberdeen,Washington: September 1986–March 1987

Chapter 7: Soupy Sales in My Fly - Raymond,Washington: March 1987

Chapter 8: In High School Again - Olympia,Washington: April 1987–May 1988Chapter 9: Too Many Humans - Olympia,Washington: May 1988–February 1989

Chapter 10: Illegal to Rock N’ Roll -

Olympia, Washington: February 1989–September

1989

Chapter 11: Candy, Puppies, Love - London,England: October 1989–May 1990

Chapter 12: Love You So Much - Olympia,Washington: May 1990–December 1990

Chapter 13: The Richard Nixon Library -

Olympia, Washington: November 1990–May 1991

Chapter 14: Burn American Flags - Olympia,Washington: May 1991–September 1991

Chapter 15: Every Time I Swallowed - Seattle,Washington: September 1991–October 1991

Chapter 16: Brush Your Teeth. - Seattle,Washington: October 1991–January 1992

Chapter 17: Little Monster Inside - Los

Angeles, California: January 1992–August 1992

Chapter 18: Rosewater, Diaper Smell - Los

Angeles, California: August 1992–September

1992

Chapter 19: That Legendary Divorce - Seattle,Washington: September 1992–January 1993

Chapter 20: Heart-Shaped Coffin - Seattle,Washington: January 1993–August 1993

Chapter 21: A Reason to Smile - Seattle,Washington: August 1993–November 1993Chapter 22: Cobain’s Disease - Seattle,Washington: November 1993–March 1994

Chapter 23: Like Hamlet - Seattle, Washington:

March 1994

Chapter 24: Angel’s Hair - Los Angeles,California–Seattle, Washington: March 30–

April 6, 1994

Epilogue: A Leonard Cohen Afterworld - Seattle,Washington: April 1994–May 1999

Source Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

Picture Section

About the Author

CopyrightAuthor’s Note

Less than a mile from my home sits a building that can send a

graveyard chill up my spine as easily as an Alfred Hitchcock

film. The gray one-story structure is surrounded by a tall

chain-link fence, unusual security in a middle-class

neighborhood of sandwich shops and apartments. Three

businesses are behind the fencing: a hair salon; a State Farm

Insurance office; and “Stan Baker, Shooting Sports.” It was

in this third business where on March 30, 1994, Kurt Cobain

and a friend purchased a Remington shotgun. The owner later

told a newspaper he was unsure why anyone would be buying

such a gun when it wasn’t “hunting season.”

Every time I drive by Stan Baker’s I feel as if I’ve

witnessed a particularly horrific roadside accident, and in a

way I have. The events that followed Kurt’s gun shop

purchase leave me with both a deep unease and the desire to

make inquiries that I know by their very nature are

unknowable. They are questions concerning spirituality, the

role of madness in artistic genius, the ravages of drug abuse

on a soul, and the desire to understand the chasm between the

inner and outer man. These questions are all too real to any

family touched by addiction, depression, or suicide. For

families en-shrouded by such darkness—which includes mine—

this need to ask questions that can’t be answered is its own

kind of haunting.

Those mysteries fueled this book but in a way its genesis

began years before during my youth in a small Washington town

where monthly packages from the Columbia Record and Tape Club

offered me rock n’ roll salvation from circumstance.

Inspired in part by those mail-order albums, I left that

rural landscape to become a writer and magazine editor inSeattle. Across the state and a few years later, Kurt Cobain

found a similar transcendence through the same record club

and he turned that interest into a career as a musician. Our

paths would intersect in 1989 when my magazine did the first

cover story on Nirvana.

It was easy to love Nirvana because no matter how great

their fame and glory they always seemed like underdogs, and

the same could be said for Kurt. He began his artistic life

in a double-wide trailer copying Norman Rockwell

illustrations and went on to develop a story-telling gift

that would infuse his music with a special beauty. As a rock

star, he always seemed a misfit, but I cherished the way he

combined adolescent humor with old man crustiness. Seeing him

around Seattle—impossible to miss with his ridiculous cap

with flaps over his ears—he was a character in an industry

with few true characters.

There were many times writing this book when that humor

seemed the only beacon of light in a Sisyphean task. Heavier

Than Heaven encompassed four years of research, 400

interviews, numerous file cabinets of documents, hundreds of

musical recordings, many sleepless nights, and miles and

miles driving between Seattle and Aberdeen. The research took

me places—both emotional and physical—that I thought I’d

never go. There were moments of great elation, as when I

first heard the unreleased “You Know You’re Right,” a song

I’d argue ranks with Kurt’s best. Yet for every joyful

discovery, there were times of almost unbearable grief, as

when I held Kurt’s suicide note in my hand, observing it was

stored in a heart-shaped box next to a keepsake lock of his

blond hair.

My goal with Heavier Than Heaven was to honor Kurt Cobain

by telling the story of his life—of that hair and that note

—without judgment. That approach was only possible because

of the generous assistance of Kurt’s closest friends, his

family, and his bandmates. Nearly everyone I desired to

interview eventually shared their memories—the only

exceptions were a few individuals with plans to write theirown histories, and I wish them the best in those efforts.

Kurt’s life was a complicated puzzle, all the more complex

because he kept so many parts hidden, and that

compartmentalization was both an end result of addiction, and

a breeding ground for it. At times I imagined I was studying

a spy, a skilled double agent, who had mastered the art of

making sure that no one person knew all the details of his

life.

A friend of mine, herself a recovering drug addict, once

described what she called the “no talk” rule of families

like hers. “We grew up in households,” she said, “where we

were told: ‘don’t ask, don’t talk, and don’t tell.’ It